It may seem like only yesterday for the team, but Yorkshire based studio, Revolution Software, are 25 years old as of today. Best known for their pioneering work on Broken Sword and Beneath a Steel Sky, we got the chance to sit down with Charles Cecil, one of the co-founders of the studio, to talk about his time in the games industry, from humble beginnings to adventure game masters, and what's next for the team:

The man himself

Can you tell us a little bit about how the company came into being? About the early days of Revolution Software?

I actually wrote my first game for the Sinclair ZX-81 back in 1981, which was a text adventure for a company I was one of the owners of, called Arctic Computing. I think we might have been the first European games company! At the time it felt quite lonely, quite pioneering, and I'd love to find out if we were actually the first! I wrote a number of adventures for Arctic, then went to work for US Gold, then Activision, and around about 1989, Activision started running into trouble. The US side was losing a lot of money, and it was clear the company was in financial trouble globally. Having worked for US Gold, I was dying to get back into development, and my boss at the time came and said "I'm really sorry, we're going to have to make you redundant - but would you be prepared to work for four months, for two or three days a week". And I looked at him, in utter disbelief at how lucky I was to have this opportunity to set up a new development company, while actually, quite legitimately working for my previous employer.

And that happened about the same time as a very good friend, Shaun Brennan, was working for a company called Mirrorsoft, and drove down to see me to say, "if you wanted to start a development company, Mirrorsoft would be very keen to review your games, and would love to support you"

So these two things together gave me the perfect opportunity. My girlfriend at the time, Noirin Carmody was running Sierra for Activision, and a colleague of mine, Tony Warriner, who I worked with at Arctic, was very keen to get back in development, and he was working for an aeronautical software company with a friend of his, David Sykes. So I called the four of us together, and decided to set up a new software company. And that was the beginning!

Sounds like a lot of serendipity and luck, then!

There was a lot of luck, yeah. I mean, I loved the idea of moving the adventure genre forward. Back in the 1980s, the adventure genre was the most innovative genre. It was innovative in terms of technology, it was innovative in terms of how a narrative could be conveyed, and it was a particularly exciting place to be. Hardware manufacturers were excited to have adventures, because adventures needed lots of memory, voices, and creatively they broke new boundaries. What I loved the idea of was that you could have a world where characters walked around and talked to each other, and where if you told a character one thing, they might pass it on to someone else. That was the sort of vision. So we came up with a system called virtual theatre.

Tony and Dave worked away in a tiny, tiny room above a sweet shop in Hull - and it was so cold, that the first piece of equipment we bought, beyond the PC and the Atari ST, was a small gas heater. But the heater was a gas heater, and the room was so small that the gas that came out - the carbon monoxide - was actually so dangerous, they had to open the window, let the freezing air in, and let the carbon monoxide out. And that was our humble beginnings as a company.

The second bit of serendipity is a meeting that followed. Shaun and Mirrorsoft wanted to review the game, and they drove down to Hull, and we were meeting in London, because I had a flat in London. I insisted that my 386, of which I was incredibly proud, because it was such a fast, beautiful computer with lots of memory, would go in the back of the car - but with a seat belt round it. And a blanket!

So we stuck the seat belt around and the blanket, got to where we were going, and went inside. Then the big day arrived, and I went to get something out the car, and I realised someone had broken in - and at that moment, I realised we'd forgotten to unpack the PC. Now, this was a PC that cost, I think something in the region of £2,000 back in 1988 - it was absolutely top of the range, and the colour drained from my face, because we could never have afforded to buy a new PC. So I went to the car, looked inside, and the car radio was gone, but guess what was still sitting on the back seat, strapped in? And as they say, the rest is indeed history.

You say your very first game was on the ZX-81. That must have been the very, very early days of software development, the truly pioneering stuff. I imagine this is back in the days where you'd write it onto a tape cassette, and then sell it to the local shop

Well, what it was more like was I'd design it on graph paper first, and then write stuff down, because nobody typed - not back then. I'd then give Richard lots of notes, and he'd program it. At Arctic, we were the first people to crack WH Smith. WH Smith was the big retailer at the time, and we had to try to pretend to be grown up! Back in those days, when you made a phone call, it'd go beep beep beep beep and you'd have to put 10p in. We didn't have a phone in the student flat - because we were students - and I was really worried about how I was going to phone without the beep. But about a mile into the city centre in Manchester, there were these modern phones that you could put 10-20p in, in advance, so it didn't go beep beep beep, and that was an absolute god send.

So I'd phone up WH Smith, tell them we have a new game, similar to adventure A, B and C, and he'd say "Oh yeah, send us 5,000". So, 5,000 at £5 each - I think they were selling at close to £5 each - from WH Smiths alone, you'd have £25,000. Then you'd phone up the tape duplicator company, and ask them to duplicate 5,000, we'd phone our printers in Hull and get them print 5,000 and send them to tape duplicating company, and by the time the tape duplicating company had finished, the printers would have sent the inlays by courier to them, and they'd send it on to WH Smiths.

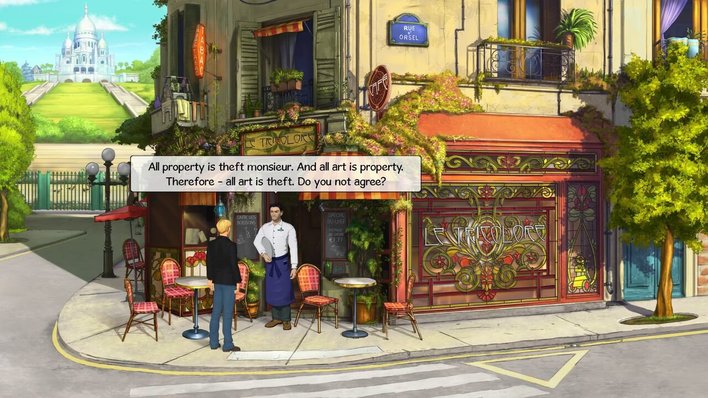

The Broken Sword games have always had an international flair

I think, one of the things a lot of people may not realise is that Revolution are very much a British company. You guys are based in York - do you think a lot of people may not know that Broken Sword games come out of the UK?

I think we have British sensibility - we try very hard not to offend anybody (well, not offend anybody unnecessarily). We aim our games to be "parental guidance" - sometimes they get rated at 12, sometimes even at 16. If they were films, they'd be absolutely PG, through and through, but I think games are judged a fair bit harder than films are. But certainly our objective is to write totally international games that will appeal across a broad range of audiences.

And one of the great things about the genre is that we get the most wonderful stories back from people who've played them together, whether it be a husband and wife, or children with their parents. I mean, just recently, we got an email from someone who started off "I'm sure no-one will read this, but", and he was quite excited we were making a new Broken Sword game. And he described how his grandmother took him into a games shop 20 years ago, and asked him to pick a game, and he picked Broken Sword. And he described how he'd rush back to her house after school, and they'd play the game together, and whenever he got stuck, he'd phone her up, and she'd try and help. And this adventure game defined, in a way, the relationship between a young boy and his grandmother. And I'm very proud that our medium offers these opportunities, in a way that, a film, or a book wouldn't. The ability to co-operate in this way, and how profoundly it can affect people, is unique to the medium.

Broken Sword was one of the games at the golden age of point and click adventure games, and I'd love to get your thoughts on where the genre stands today. Certainly when I was growing up, point and click/adventure games were everywhere, first on the Amiga, then the PC, and now things seem to have moved to tablets, so what's your take on the genre today?

Well, we've produced Broken Sword 5 on mouse for PC, Mac and Linux, touch screen for Android, iOS and Vita, and controller for PS4 and Xbox One. We're blessed that actually, the control interface moves quite seamlessly across those three input devices. For us, all three areas are really important, and it's fantastic that the genre also appeals across audiences, as those who play games on tablets are quite different to those who play on consoles. You may remember that we crowd funded Broken Sword 5, and if you add in the Pay Pal numbers, we raised $850,000, which is great - but every bit as good was having a community of 15,000 people with whom we could communicate. The ability to communicate on a regular basis with those people, and have those people evangelise on our behalf was fantastic, because it means a small team like Revolution can compete, very effectively, with EA, or Ubisoft.

That was one of the things I was going to ask about - what are your thoughts on moving from the more traditional publishing model to a kickstarter model instead. Is it that publishers weren't willing to take a risk, or was it something else entirely?

Well, we are still very much working with publishers, in that Koch are doing our boxed copies of Broken Sword 5 across Europe, and will be publishing the 25th anniversary bundle, which is very valuable. But it comes down to a business sense - whoever takes the risk is going to take the vast majority of the rewards. In the traditional retail model, the developer would get about 7% of revenues, against which would be offset all development costs, some of the QA, and anything else the publisher thought was a legitimate publishing cost, which ultimately meant that pretty much never ever would the developer recoup. So you'd be in a position where you're making games that retailers would make many millions of dollars publishing, and retailers would make millions of dollars, yet you could easily find yourself making quite a substantial loss. It was utterly unsustainable. So, the ability to self-publish - which does require the developer to self-fund as well, so it's not quite a nirvana - if you can get into that position, then all of a sudden you get 70%, against which you deduct your costs. So effectively you're getting 10x as much, for taking the risk, and it means if the game's reasonably successful, you will recoup, whereas under the traditional model, even if the game's successful, you would not.

With logic like that...

7% is a very slim margin to try and survive on!

To be fair, that is the retail price, so the retailer takes roughly half, the publisher gets just over half, but then deduct the cost of goods before paying the royalty, so it was an unsustainable model for an independent developer - and a lot of credit has to go to Apple for seeing the opportunity to publish digitally as they were. Microsoft, Sony, Google and Apple are incredibly indie friendly, which is fantastic, and of course Steam on PC. It basically levels the playing field, which was extremely uneven when we were trying to compete and the main route to our audience was through retail.

I was wondering if you thought there was a disconnect between what the publishers think people want, and what they actually want, as shown through kickstarter?

The problem is, the cost of games rose so high, so quickly, and the reason is probably because the PlayStation was so successful that retailers started stocking more and more PlayStation titles over PC games, which was one of the reasons why the mantra was "PC is dead". So, publishers started really competing to become one of those slots, and publishers found themselves wanting to support and fund games that they had reasonable confidence, in 18 months time, when the game finished, a retailer would stock it. In other words, there were so many variables, and so much risk-adversity, that ultimately what publishers wanted to fund was exactly the same game they funded before, but changed slightly. So, we went through a period where there was a total lack of innovation. At one of the US publishers I worked for, the chief executive was so proud of the fact he'd never played a game, he believed that was what gave him the insight to judge better than gamers, what gamers wanted, because he'd never played a game. And I'm not joking, or in any way exaggerating. And that was kind of what led to genres like the interactive movie, because people like him decided that what people wanted wasn't to really play games, but to play movies, but control the outcomes. So huge amounts of money went into interactive movies, which, of course, were deeply unsatisfactory. Clearly there were some publishers that were very talented - when we worked for Virgin, they had a fantastic instinct, and a deep and utter respect for their audience - but that was at odds to those people who were running a lot of the companies, who were accountants, and had no respect for those playing the games

One of the questions I was going to ask was, Broken Sword 5 game out on PS4 and Xbox One - why are more games like that not coming out on what you'd call the traditional console formats?

What a good question! The difference between Broken Sword and most adventures is that we have very high production values - and the games are very expensive to write, in truth. I think that means we're probably more welcome, because of the high production values, than adventure games that are made on a much lower budget, and don't look so good. Clearly, the traditional PC audience, you'd consider would be more enthusiastic about adventures than the traditional console audience, although I have to say, we're absolutely thrilled with the reception the game received from the PS4 and Xbox One community, but I probably suspect that Sony and Microsoft probably suspect that it's not as mainstream on their platforms as it would be on PC.

There's no special hurdles to get over, or anything you need to do for approval?

None whatsoever. We're blessed with very talented programmers, but it was a job that took two programmers six months, and they did a great job! But Microsoft and Sony couldn't have done much more to help us - they were both fantastic.

Looking back on the last 25 years of Revolution Software, what's next?

Well, we're actually in a great position. We have a sizeable community who tell us that they're very pleased with the way the kickstarter ran. We delivered the game we said we would - it was a little bit late - but we communicated all the way through, and as long as you're open about why there are delays, people come along. We would certainly want to consult with them on any major creative decisions, because these are the people we hope who would be buying our games, and evangelise on our behalf, and we may well want to go down a kickstarter/crowd-funding route again.

As far as what happens next, we're working on an original game. We're talking to Dave Gibbons, the comic book artist behind Watchmen, and we're talking about doing a project with him - and at some point, I've got some really nice ideas for a new Broken Sword game. So we're in this fantastic position of more projects we feel are strong than we can actually handle!

I guess the only other question is, is there anything else about the Beneath a Steel Sky sequel?

Well, we're talking to Dave about a new game, so who knows!